What is dialogue in writing? What are examples of dialogue in writing? What are examples of dialogue conversations? Often, writers use dialogue to show how characters relate to one another. The idea of dialogue is mostly how it sounds, conversation (or small talk). Though, most often, characters in a story will have dialogue with each other. And it’s important to learn how they should get written and what the best forms of dialogue are to make your readers comprehend the subject.

What Is Dialogue?

A dialogue is nothing more than an exchange of words between two or more people.

To be precise, the word “dialogue” comes from the Greek word “dialogos.” “Dia” means “through,” and “logos” means “word” or “reason.”

Plato likened dialogue to a stream of meaning flowing between and through people, which would emerge new meanings or understandings. He introduced philosophy to the masses through his dialogues, which you can read more about here.

Renowned painter Erik Pevernagie once said, “A world without dialogue is a universe of darkness.”

He strongly believed that sharing your views and ideas through dialogue allows you to understand the world and appreciate its beauty.

Dialogue is the most fundamental way that human beings communicate.

In literature, dialogue is what allows us to see characters fight, debate, love, and reconcile with one another.

Famous Examples of Dialogue From Literature

The Maltese Falcon – Dashiell Hammett (Dialogue Example)

Spade grinned sidewise at her and said, “You’re good. You’re very good.”

Her face did not change.

She asked quietly, “What did he say?”

“About what?”

She hesitated.

“About me.”

“Nothing.”

Spade turned to hold his lighter under the end of her cigarette. His eyes were shiny in a wooden Satan’s face.

To Kill A Mockingbird – Harper Lee (Dialogue Example)

“What are you all playing?” he asked.

“Nothing,” said Jem.

Jem’s evasion told me our game was a secret, so I kept quiet.

“What are you doing with those scissors, then? Why are you tearing up that newspaper? If it’s today’s, I’ll tan you.”

“Nothing.”

“Nothing, what?” said Atticus.

“Nothing, sir.”

“Give me those scissors,” Atticus said. “They’re no things to play with.

There are too many passages in books filled with dialogues worth quoting. You can read more here.

How to Write Dialogue (in a story or otherwise)

Different authors have different opinions on what makes a piece of dialogue click. But there are general rules you must keep in mind to ensure your dialogue is easily understood and leaves an emotional impact on readers.

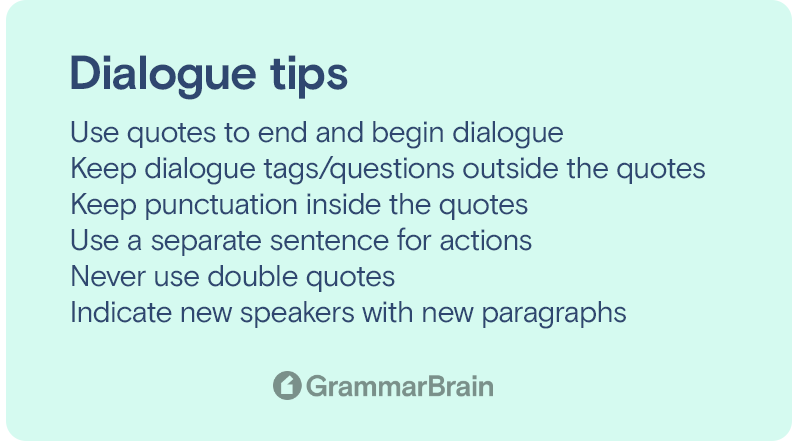

1. Use quotation marks to end and begin your dialogue.

“Like this?”

“Exactly so.”

Quotation marks are where your character’s voice begins. This simple bit of punctuation brings life to a dull block of prose that would otherwise be soulless and characterless.

“That was easy enough. So what’s next?”

Closing quotation marks should end the single dialogue in the lines of dialogue that make up the conversation between two characters.

2. Keep your dialogue tags outside the quotation marks.

A dialogue tag is what tells your readers that a line of dialogue belongs to a specific speaker.

“Is this what you mean?” asked Alice.

“That is exactly what I mean,” said Bob, nodding.

“What about this asked Alice?”

“Now I have no idea how to read what you said,” said Bob.

3. Keep your punctuation inside the quotation marks.

As a rule of thumb, if you write the dialogue tag first, you want to bring the comma before the quotation mark.

But what if you use an exclamation mark or a question mark?

“Like this one?” asked Bob.

“Yes, exactly like that,“ said Alice.

In this situation, you write the following dialogue tag in lowercase instead of uppercase.

“Oh, God, punctuation! My mortal enemy!” said Alice, shaking her fist at the skies.

Very good, Alice.

Tip: If your line of dialogue ends in an exclamation point or question mark, the tags that follow should be in lowercase.

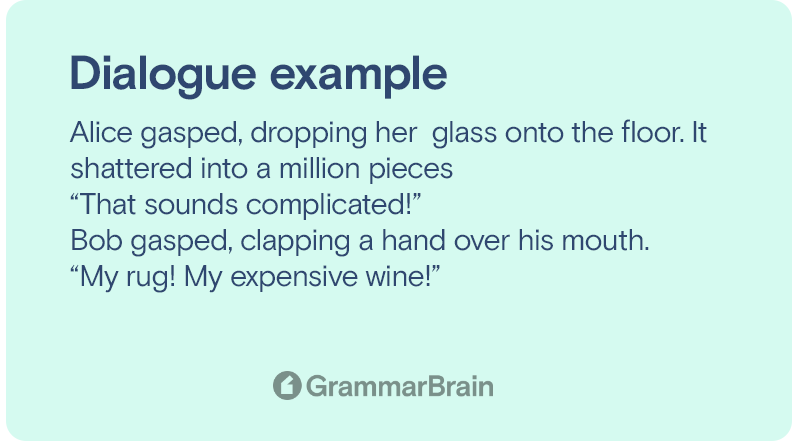

3. Use a separate sentence for actions that happen before and after your dialogues.

Any action or movement should be given its own sentence next to your dialogue.

Alice gasped, dropping her glass onto the floor. It shattered into a million pieces.

“That sounds complicated!”

Bob gasped, clapping a hand over his mouth.

“My rug! My expensive wine!”

4. Never use double quotes inside dialogue. Use single quotes instead.

If your character is quoting someone else, make sure you use single quotes, or your text will quickly get confusing.

“I remember a nice Englishman that once said, ‘To be or not to be,’” said Bob, “But I don’t remember the question.”

5. Indicate new speakers with new paragraphs.

Every time you change a speaker, you must start a new paragraph. If you are writing a manuscript, you must also indent the paragraph.

If your character performs an action, keep the action in the same paragraph. Only then should you move to the following line in the next paragraph when you bring in your new speaker.

“We’re all out of wine!” said Alice. She pointed at the empty bottle in her hands.

“Can you please not break any more glasses?” said Bob as he gingerly picked up pieces of shattered glass with gloved hands.

6. Every time an action interrupts your dialogue, begin with lowercase again.

“At the end of the day,” Alice whispered to herself, placing the bottle tenderly on the table, “why does all the wine disappear?”

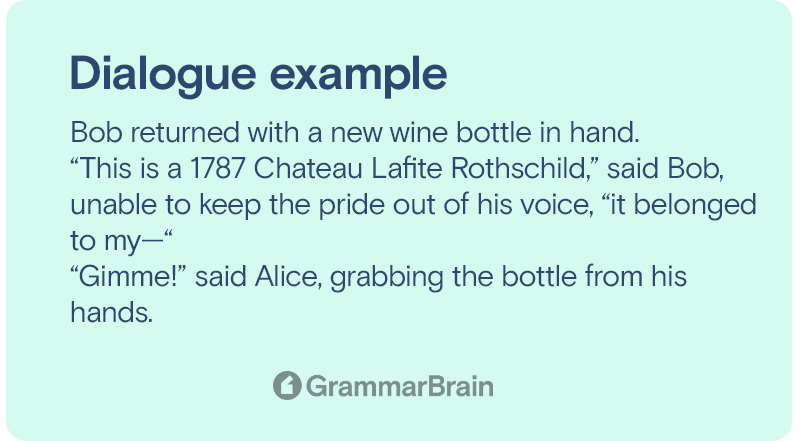

7. Indicate an interruption with an em dash.

Em dashes are not the same as hyphens. They are used to show readers that a line of dialogue has been cut off mid-sentence.

You should always place your dash inside the quotation marks, just as you would with all other punctuation marks. If you’d like a refresher on the difference between an em dash and a hyphen, read this.

Bob returned with a new wine bottle in hand.

“This is a 1787 Chateau Lafite Rothschild,” said Bob, unable to keep the pride out of his voice, “it belonged to my—“

“Gimme!” said Alice, grabbing the bottle from his hands.

Writing Dialogue: Identifying a Speaker

Not all dialogue needs dialogue question.

“Really?”

“Yes. Really.”

But when you use a dialogue question, you must use a comma. You must place a comma, quotation, and dialogue tag, in that order.

Any punctuation in the sentence must come inside the quotes.

“You know,” said Alice, “I think I’m starting to get the hang of this.”

What if you don’t want to put the dialogue tag in the middle of the sentence? You must identify the speaker in advance by bringing attention to an action or gesture before writing their dialogue.

Bob sighed, settling into this chair.

“I’m happy to hear that, Alice.”

Sometimes, you will identify the speaker explicitly.

“And by explicit, you mean telling the reader outright who is speaking, right?” said Alice.

Sometimes, you will identify the speaker implicitly.

“That is exactly what that means, Alice, dear, yes.”

The above dialogue does not have the speaker referenced by name. But with the help of context and preceding dialogue, we can tell exactly who is speaking.

At other times, we will identify the speaker through anaphora.

“What does anaphora mean?” asked the clumsy yet enthusiastic lady.

“It means indirectly identifying the speaker without using their name, dear,” came the unhappy man’s response.

Other times, you can identify the speaker even when a dialogue tag is not used. This happens when the dialogue directly refers to the person being spoken to, making the speaker obvious.

“I’m referring to you now, Alice.”

“I know, Bob, you don’t have to tell me.”

Readers get tired of the whole “he said,” “she said,” business if it’s overdone. You want to juggle different methods of identifying the speaker as you write, making sure to sprinkle in clues about who the speaker is.

This prevents stale and overdone writing. It adds spice to an otherwise repetitive piece of prose and breathes life into the text.

How To Format Dialogue (Formatting Dialogue Examples)

When writing a manuscript, begin the first line of each paragraph indented.

If using British English, use single quotation marks.

If using American English, use double quotation marks.

But whatever the region, enclose the spoken words inside the quotation marks.

“Quotes are the best way to tell your readers someone is talking.“

“I know, Alice.”

“Why do Americans use double quotes instead of single quotes, Bob?”

Bob shrugged.

“That’s just the way it is. The same reason the English add the letter ‘u’ in many of their words while Americans don’t.”

(If you’d like to read an expert’s opinion on why different regions use single and double quotes, read this)

Always keep dialogue tag/questions out of your quotes

“But enough about grammar, Alice,” said Bob, sinking into his chair.

“Look at the nice weather we’re having.”

“I can see the sun for once, yes,” said Alice.

“What a sight to behold,” said Bob, smiling.

Don’t forget to use lowercase when following up a dialogue tag that has a quotation or exclamation mark.

“On the whole, this has been a surprisingly good day, don’t you think?” said Alice.

“Except for the part where you spilled my expensive wine all over the carpet!” shouted Bob.

There was a pause as Alice sank into her chair.

“Sorry.”

Make sure that all actions before and after the dialogue go into a separate sentence.

Alice placed the glass to her lips.

“Hey, this isn’t half bad!”

Bob smiled, pointing to the bottle he’d set on the table.

“It was my grandfather’s. I’m glad you like it.”

Make sure to place all punctuation inside the quotes

“I’m sorry,” said Alice, setting her glass down, “I was just excited.”

“No, no,” said Bob, waving a dismissive hand, “don’t worry about it.”

The ellipsis deserves a special mention here. If you end any dialogue with an ellipsis, make sure not to add further punctuation, such as a comma after it. (For some extra tips on formatting your dialogue, read this.)

For instance, you would never write:

“I miss granddad…,” said Bob, his eyes misting over.

You would instead write:

“I miss granddad…” said Bob, his eyes misting over.

Always place single quotes within double quotes when referencing something from an outside source. This includes famous proverbs, cliches, and dialogues that other characters in your story have used in the past.

“’Save it for a special one, boyo,’” said Bob, smiling, “that’s what my granddad said when he gave me that.”

Start a new paragraph when changing speakers.

“What’s special about today?” said Alice, tilting her head.

“You don’t remember?” said Bob.

“No,” said Alice.

“Are you serious?” said Bob.

Alice frowned, trying to remember. She looked up at him and shrugged.

Writing Compelling Dialogue

1. Subtext is king.

People in real life often have wide gaps between what they say and think. There are also gaps between what a character understands and what they refuse to hear.

Two characters that know each other often have more unspoken dialogue than spoken dialogue. These are vital and valuable territories that writers can take advantage of to create drama and tension.

2. Good dialogue advances the plot and reveals character.

Characters speak for a reason. Desire forces characters to interact; through this interaction, we witness the unraveling of events and scenarios.

These events either push them away or toward achieving the story’s primary goal. Dialogue is also best to show how your characters feel instead of just telling your readers how they feel. You introduce context through dialogue and use it to reveal how a character thinks about someone.

3. Dialogue reflects your character’s background.

Each person has their way of speaking. A brute and a scientist have noticeably different syntaxes of speech where readers can peer into their thought processes by examining the words they use and how they say them.

Social class, upbringing, personality, and coping mechanisms also factor into how a character speaks.

4. Keep your dialogue tags simple.

The most straightforward dialogue tags are often the best. While many critics believe that writers should never use words other than “said,” others believe it’s okay to have a little variety.

A few dialogue tags like “called” or “muttered” can be illustrative and draw attention to critical moments and emotions.

Others believe mentioning a single adverb is an outright sin, but they have their place in descriptive prose. You can read more about writing engaging dialogue here.

Internal Monologue Versus External Dialogue

An internal monologue is nothing more than the character’s innermost thoughts that the writer is exposing to the audience. This monologue contains the character’s voice and serves as a way for readers to understand the character’s thought processes better.

This monologue does not reveal every thought the character has but is used to display selective emotions and thought processes in response to meaningful story events.

An internal monologue is not omniscient in the same way that a narrator’s exposition is.

External dialogue is the words exchanged between two or more characters. These are words that are being spoken out loud.

This dialogue is often accompanied by dialogue tags, action tags, and descriptions.

If you’d like to learn more about how to create a compelling internal monologue, read this.

How to Punctuate Dialogue Correctly

Literary dialogue has its own rules for punctuation. In most instances, commas, periods, question marks, and exclamation marks go inside the quotations.

“It’s a beautiful and happy day today,” he said.

“What a beautiful day!” he said.

“Isn’t this a beautiful day?” he asked.

The one exception to this rule regards question marks.

When a character is referencing a proverb/statement/cliche that contains a question, we place the question mark outside the quotation mark to denote that it is a reference to something.

Did the professor say, “The equation goes here”?

For a more comprehensive list of rules on punctuation, read this.

When and How to Use Quotation Marks in Dialogue

The primary purpose of a quotation mark is to indicate words being spoken by a character or referenced from an outside source.

Using them in literature or formal documentation comes with specific rules.

- Always use quotation marks in pairs.

- Always capitalize the first letter of a word used verbatim in a quote.

- Don’t use capital letters when referencing only a fragment of a quote from another source.

- The period or comma always comes before the final quotation mark. The only exception to this is content written explicitly by the Modern Language Association (MLA) style guidelines.

The quotation mark has a long and fascinating history which you can learn more about here.

The Best Books to Learn Dialogue

Emulating the masters is the perfect way for beginners to learn. I’ve compiled this short list of books widely regarded as having some of the best dialogue in fiction.

Once you read these, mimic the style of the masters and add your unique flair to create your style of dialogue.

- Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

- An Ideal Husband by Oscar Wilde

- The Importance of Being Earnest by Oscar Wilde

- The Color of Magic by Terry Pratchett

- Much Ado About Nothing by William Shakespeare

- Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë

- Kiss an Angel by Susan Elizabeth Phillips

- The Secret History by Donna Tartt

While literary fiction contains some of the best dialogue, screenplays are another source of good dialogue.

Screenplays focus exclusively on dialogue, ignoring literary devices such as descriptions and dialogue tags. You can read more about writing dialogue in screenplays here.

Speak Your Story

Dialogue is an indispensable part of every story. It helps to move a story forward. One character can present new ideas to another. Helping to advance a short story or written novel. Written well helps you create memorable characters and explore fun and dramatic situations.

But poor, overly formal, stilted, or illogical dialogue can quickly drive readers away. The best way to improve your dialogue writing is to talk to more people and read more books.

Read genres out of your comfort zone to see how different stories make characters tick and transform.

FAQs

What are some dialogue examples in a story?

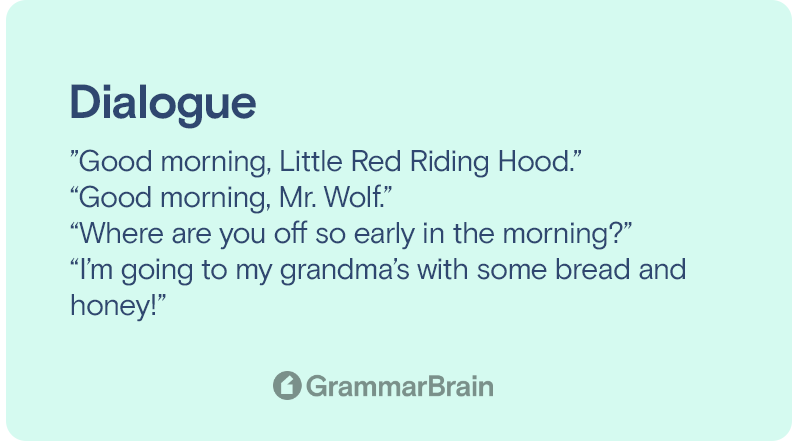

”Good morning, Little Red Riding Hood.”

“Good morning, Mr. Wolf.”

“Where are you off so early in the morning?”

“I’m going to my grandma’s with some bread and honey!”

What are some examples of “dialogue” used in a sentence?

“The dialogue in this movie is more comedy than horror.”

“Socratic dialogue is a conversation between people where questions are constantly asked to make people think critically.”

Inside this article

Fact checked:

Content is rigorously reviewed by a team of qualified and experienced fact checkers. Fact checkers review articles for factual accuracy, relevance, and timeliness. Learn more.

Core lessons

Glossary

- Abstract Noun

- Accusative Case

- Anecdote

- Antonym

- Active Sentence

- Adverb

- Adjective

- Allegory

- Alliteration

- Adjective Clause

- Adjective Phrase

- Ampersand

- Anastrophe

- Adverbial Clause

- Appositive Phrase

- Clause

- Compound Adjective

- Complex Sentence

- Compound Words

- Compound Predicate

- Common Noun

- Comparative Adjective

- Comparative and Superlative

- Compound Noun

- Compound Subject

- Compound Sentence

- Copular Verb

- Collective Noun

- Colloquialism

- Conciseness

- Consonance

- Conditional

- Concrete Noun

- Conjunction

- Conjugation

- Conditional Sentence

- Comma Splice

- Correlative Conjunction

- Coordinating Conjunction

- Coordinate Adjective

- Cumulative Adjective

- Dative Case

- Determiner

- Declarative Sentence

- Declarative Statement

- Direct Object Pronoun

- Direct Object

- Diction

- Diphthong

- Dangling Modifier

- Demonstrative Pronoun

- Demonstrative Adjective

- Direct Characterization

- Definite Article

- Doublespeak

- False Dilemma Fallacy

- Future Perfect Progressive

- Future Simple

- Future Perfect Continuous

- Future Perfect

- First Conditional

- Irregular Adjective

- Irregular Verb

- Imperative Sentence

- Indefinite Article

- Intransitive Verb

- Introductory Phrase

- Indefinite Pronoun

- Indirect Characterization

- Interrogative Sentence

- Intensive Pronoun

- Inanimate Object

- Indefinite Tense

- Infinitive Phrase

- Interjection

- Intensifier

- Infinitive

- Indicative Mood

- Participle

- Parallelism

- Prepositional Phrase

- Past Simple Tense

- Past Continuous Tense

- Past Perfect Tense

- Past Progressive Tense

- Present Simple Tense

- Present Perfect Tense

- Personal Pronoun

- Personification

- Persuasive Writing

- Parallel Structure

- Phrasal Verb

- Predicate Adjective

- Predicate Nominative

- Phonetic Language

- Plural Noun

- Punctuation

- Punctuation Marks

- Preposition

- Preposition of Place

- Parts of Speech

- Possessive Adjective

- Possessive Determiner

- Possessive Case

- Possessive Noun

- Proper Adjective

- Proper Noun

- Present Participle

- Prefix

- Predicate