Commas are one of the trickier punctuation marks to get right. Here’s the thing: commas are critical to to writing well. It’s certainly worthwhile learning how to use commas correctly, especially when it comes to whether or not to use a comma before but (since this is a grammar rule that will pop up time and time again).

Learn the proper usage of when to put a comma before but (and after) to ensure the writing flows.

Back to the basics: what’s a comma?

Commas are a form of punctuation in English grammar and arguably one of the most frequently used (and abused) punctuation marks in English writing.

A comma looks like this: ‘,’ Commas dictate the writing flow for the reader.

When commas appear in writing, this indicates to the reader that they should take a pause or soft break (either to take a breath, to add sequential logic and/or emphasis).

This is different from a period, which signifies a full stop in a complete sentence. There are numerous punctuation marks in English grammar, such as the semi-colon; colon: em dash—, and an exclamation mark! And the list goes on.

To master how to use the comma correctly and other key writing tips, keep reading.

When do you need to use a comma before but?

Answer: when there are two independent clauses conjoined with but, use a comma. Otherwise, in sentences where there is one standalone clause, do not use a comma. Sentences with two independent clauses conjoined with coordinating conjunction need a comma.

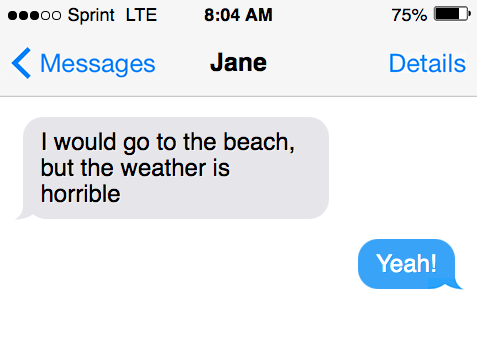

Correct: “I would go to the beach, but the weather is horrible.”

Correct: “I would go to the beach, but the weather is horrible.”

Incorrect: “I would go to the beach but the weather is horrible.”

Incorrect: “I would go to the beach but the weather is horrible.”

An independent clause is a sentence that stands on its own and forms a complete thought or idea. This is the opposite of a dependent clause, which relies on a full clause to be correct. must contain a predicate and verb.

Take a look at the following sentences, which are all examples of independent clauses:

- “Sarah is at the bus stop.”

- “Mark wants to get a puppy.”

- “The moon orbits around the Earth.”

- “I’m going to the cinema.”

- “The weather is nice today.”

- “He’s wearing corduroy pants.”

The above examples are independent clauses that don’t need a comma since they are not conjoining two independent clauses through the use of but, and so forth. This is the key to understanding and distinguishing when to use a comma before but: when conjoining two independent clauses that use the coordinating conjunction ‘but.’

When do you need to use a comma in general?

There are eight basic rules to learning the correct use of commas. This article focuses on one of those rules: the use of the comma in separating independent clauses with a coordinating conjunction. In general, anytime but, so, or, is in a sentence that connects two independent clauses requires a comma.

But, so, for, etc., connect full thoughts, phrases and/or related clauses that can stand alone.

The following are all of the coordinating conjunctions:

- For

- And

- Nor

- But

- Or

- Yet

- So

Quick tip! Use the mnemonic FANBOYS to easily and readily remember each coordinating conjunction.

BASIC COMMA RULES

Commas are also used after introductory clauses or phrases or to separate items in a series or list. Commas are also used to offset appositives.

Sentences that use a comma before but examples

These sentences demonstrate the correct use of ‘but’ to connect two independent clauses through commas.

“I would go to the beach, but the weather is horrible.”

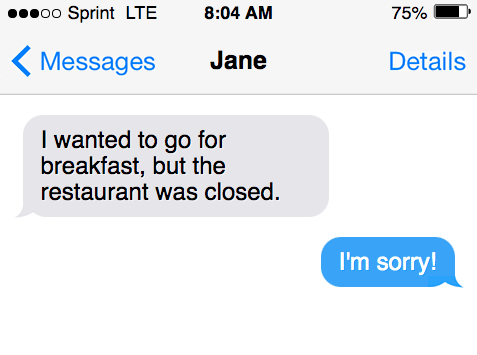

“I wanted to go for breakfast, but the restaurant was closed.”

“Mary doesn’t like fish, but her brother loves all fish”

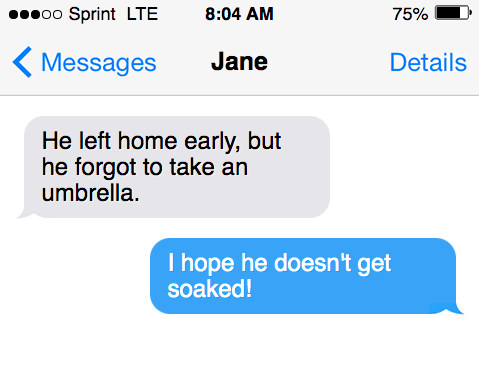

“He left home early, but he forgot to take an umbrella.”

“I meant to buy some bread, but I forgot to stop off at the bakery.”

These sentences all contain a standalone clause and complete sentences connected through the ‘but.’ The examples above each contains two complete sentences or full stops. To see this, try separating the two clauses from each other.

For example, in the sentence, “I wanted to go for breakfast, but the restaurant was closed.” It’s easy to separate these clauses to complete two individual sentences. “I wanted to go for breakfast. The restaurant was closed.”

Writing this way is still grammatically correct; however, it reads awkwardly and sounds stiff. Try reading out loud to get a feel for the rhythm of writing, so it becomes obvious which points get stiff or overly congested.

This is precisely why we use things like coordinating conjunction, commas and other forms of punctuation (to dictate the flow and intonations of the written word).

Sentences that do not need a comma before ‘but’ examples

The comma is peculiar, especially when it comes to using a comma before or after ‘but.’ Sentences that use ‘but’ but only contain one independent clause do not need a comma before but.

Here are some examples that include but, yet don’t need a comma to be correct:

“Her eyes were kind but sad.”

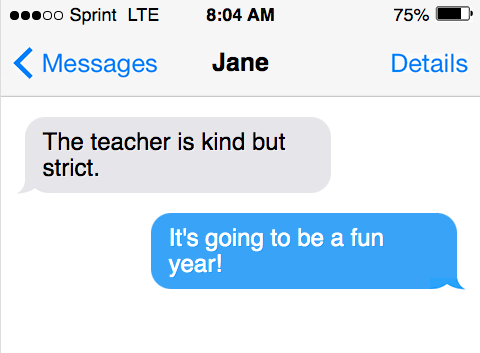

“The teacher is kind but strict.”

“I would buy a new car but for the cost.”

Each of these uses the conjunction ‘but.’ Nevertheless, they do not need a comma before ‘but’ since they only have one stand-alone thought.

As a rule of thumb on whether to include a comma, try separating the two. If it cannot form two clauses or standalone sentences, don’t include a comma.

Does a comma go after but?

Generally speaking, most times it is not necessary to include a comma after but. That said, there are times when commas are needed after but.

This is when but is immediately followed by an interrupter, i.e., “a short word or phrase that interrupts a sentence to express emotion, tone, or emphasis.”

Here’s an example:

“Margaret Thatcher was, as they say, a formidable woman.”

“Nurses do, in fact, change lives.”

“Ashley was, as they say, in the family way.”

For interrupters to function, they need, as one would guess, commas, parentheses, hyphens and/or—the em dash. Interrupters should be accessorized by one of these punctuation marks on both sides (i.e., to frame the interrupter or thought).

An effective way to recognize whether a clause includes interrupters is to see if it still makes sense absent the interrupter (or if the clause reads properly when the interrupter is removed).

Consider these variations of the above eliminating interrupters:

“Margaret Thatcher was a formidable woman.”

“Nurses do change lives.”

“Ashley was in the family way”

The clauses are grammatical even though the interrupter has been erased. This is how to confirm that it is, in fact, an interrupter in the clause.

More examples that use ‘but’ as interrupters:

“Learning grammar is hard, but, of course, it is necessary.”

“Cooking takes patience and time, but, as most would agree, the payoff is worth the effort.”

“Earning a Bachelor’s degree is not easy, but, these days, it’s tough to get by without it.”

The above clearly shows how interrupters interrupt: they wedge an additional thought into an already standalone sentence or clause (and use punctuation rules to open and close the subordinate clause).

It’s worth noting that sometimes a comma will appear after but, though usually after an introductory clause.

As before, when we move the interrupting phrase from the clause, the sentence remains coherent.

More examples:

“Learning grammar is hard, but it is necessary.”

“Cooking takes patience and time, but the payoff is worth the effort.”

“Earning a Bachelor’s degree is not easy, but it’s tough to get by without it.”

Notice how once the interrupter is removed, the second comma is no longer necessary. That’s because unless there is an interrupter directly in the clause, there is no need for a second comma after the but.

As a general rule, a comma is only used before ‘but’ to connect independent clauses and sometimes, to frame interrupting phrases. Otherwise, do not use a comma after the but.

Origin of the word ‘comma’

The comma comes from the Greek, Komma, which translates to cut off, from the Greek ‘koptein‘.

Glossary terms

Interrupter: Phrases or terms wedged into a sentence through parentheses, commas or hyphens.

Independent clause: A standalone sentence that contains a full thought.

Complete sentence: Includes a subject and predicate and a full thought or idea.

Dependent clause: An incomplete sentence that contains a subject and a verb, though is not a complete thought, is a dependent clause.

Coordinating conjunction: But, for, and yet, are coordinating conjunctions which tie two independent clauses in a single sentence.

Mnemonic: A memory aid, usually in the form of a rhyme or acronym, that helps to remember what abbreviations stand for.

Punctuation mark: Any grammatical symbol of punctuation rules

Comma: A punctuation mark indicates a pause between parts or a break in a sentence.

Exclamation mark: A type of punctuation intended to add emphasis and often used as an interjection.

Semi-colon: Symbols of punctuation rules are often used to connect two independent thoughts.

Em dash: Sometimes referred to as the mutton or em rule, this symbol is longer than an en dash and is often used in the place of parentheses (in more conversational formats of writing, like blogs.)

Introductory clause: Normally found at the beginning of a sentence and is a dependent clause.

Lesson in review

As far as grammar rules go, comma usage is one of the trickiest to nail. However, as it has been explained in this article, here are the basic rules of when to use a comma before ‘but’:

- Comma rule: Two whole sentences that use the word but need a comma before the but.

- Comma rule: If the clauses are independent and dependent, do not use a comma.

- Comma rule: It’s fine to use commas before and after interrupting phrases.

Sources

- Definition of Mnemonic: vocabulary.com

- Definition of Comma: merriam-webster.com

- Definition of Punctuation markmerriam-webster.com

- Definition of Coordinating conjunction: cuyamaca.edu

- Article on components of a sentence: evansville.edu

- Article on introductory clause: grammarly.com

Inside this article

Fact checked:

Content is rigorously reviewed by a team of qualified and experienced fact checkers. Fact checkers review articles for factual accuracy, relevance, and timeliness. Learn more.

Core lessons

Glossary

- Abstract Noun

- Accusative Case

- Anecdote

- Antonym

- Active Sentence

- Adverb

- Adjective

- Allegory

- Alliteration

- Adjective Clause

- Adjective Phrase

- Ampersand

- Anastrophe

- Adverbial Clause

- Appositive Phrase

- Clause

- Compound Adjective

- Complex Sentence

- Compound Words

- Compound Predicate

- Common Noun

- Comparative Adjective

- Comparative and Superlative

- Compound Noun

- Compound Subject

- Compound Sentence

- Copular Verb

- Collective Noun

- Colloquialism

- Conciseness

- Consonance

- Conditional

- Concrete Noun

- Conjunction

- Conjugation

- Conditional Sentence

- Comma Splice

- Correlative Conjunction

- Coordinating Conjunction

- Coordinate Adjective

- Cumulative Adjective

- Dative Case

- Determiner

- Declarative Sentence

- Declarative Statement

- Direct Object Pronoun

- Direct Object

- Diction

- Diphthong

- Dangling Modifier

- Demonstrative Pronoun

- Demonstrative Adjective

- Direct Characterization

- Definite Article

- Doublespeak

- False Dilemma Fallacy

- Future Perfect Progressive

- Future Simple

- Future Perfect Continuous

- Future Perfect

- First Conditional

- Irregular Adjective

- Irregular Verb

- Imperative Sentence

- Indefinite Article

- Intransitive Verb

- Introductory Phrase

- Indefinite Pronoun

- Indirect Characterization

- Interrogative Sentence

- Intensive Pronoun

- Inanimate Object

- Indefinite Tense

- Infinitive Phrase

- Interjection

- Intensifier

- Infinitive

- Indicative Mood

- Participle

- Parallelism

- Prepositional Phrase

- Past Simple Tense

- Past Continuous Tense

- Past Perfect Tense

- Past Progressive Tense

- Present Simple Tense

- Present Perfect Tense

- Personal Pronoun

- Personification

- Persuasive Writing

- Parallel Structure

- Phrasal Verb

- Predicate Adjective

- Predicate Nominative

- Phonetic Language

- Plural Noun

- Punctuation

- Punctuation Marks

- Preposition

- Preposition of Place

- Parts of Speech

- Possessive Adjective

- Possessive Determiner

- Possessive Case

- Possessive Noun

- Proper Adjective

- Proper Noun

- Present Participle

- Prefix

- Predicate